The Clotilda was burned and sunk in an Alabama River after bringing 110 imprisoned people across the Atlantic in 1860. Three years ago, its remains were found. Anderson Cooper reports on the discovery of the wreck and the nearby community with descendants of the enslaved aboard the ship.

Three years ago, a sunken ship was found in the bottom of an Alabama river. It turned out to be the long-lost wreck of the Clotilda – the last slave ship known to have brought captured Africans to America in 1860. At least 12 million Africans were shipped to the Americas, in the more than 350 years of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, but as we first reported in November, the journey of the 110 captive men, women, and children brought to Alabama on the Clotilda, is one of the best-documented slave voyages in history. The names of those enslaved Africans, and their story, has been passed down through the generations by their descendents, some of whom still live just a few miles from where the ship was found, in a community called Africatown.

For 160 years this muddy stretch of the Mobile River has covered up a crime. In July 1860 the Clotilda was towed here, under cover of darkness. Imprisoned in its cramped cargo hold, 110 enslaved Africans.

Joyceyln Davis: I just imagined myself being on that ship just listening to the waves and the water, and just not knowing where you were going.

Joyceyln Davis, Lorna Gail Woods, and Thomas Griffin are direct descendants of this African man, Oluale. Enslaved in Alabama, his owner changed his name to Charlie Lewis. Pollee Allen, whose African name was Kupollee, was the ancestor of Jeremy Ellis and Darron Patterson.

Darron Patterson: No clothes. Eating where they defecated. Only allowed outta the cargo hold for one day a week for two months. How many people do you, do we know now that could’ve survived something like that, without losing their mind?

There are no photographs of Pat Frazier’s great-great-grandmother, Lottie Dennison, but Caprinxia Wallace and her mother, Cassandra, have a surprising number of pictures of their ancestor, Kossula, who’s owner called him Cudjo Lewis.

Anderson Cooper: What does it feel like to be able to know where you come from? To know the person who came here first?

Caprinxia Wallace: It’s empowering, very. Like, growing up my mom made sure she told me all the stories that her dad told her about Cudjo.

Anderson Cooper: Cassandra, that was important to you to pass that knowledge along?

Cassandra Wallace: Very important, yes. My dad sat us down and he would make us repeat Kossulu, Clotilda, Cudjo Lewis.

Thomas Griffin: It has historical importance, as well as a story that needs to be told.

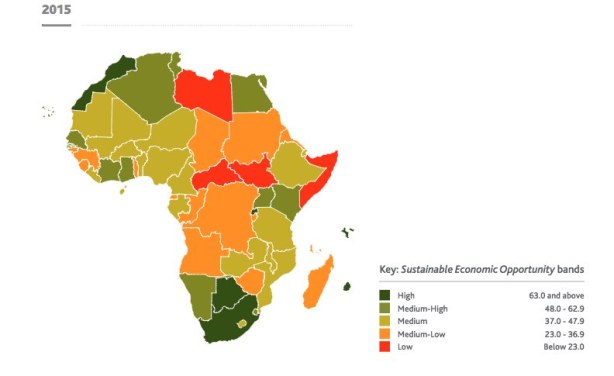

The story of the Clotilda began in 1860, when Timothy Meaher, a wealthy businessman, hired Captain William Foster to illegally smuggle a ship load of captive Africans from the Kingdom of Dahomey, in West Africa, to Mobile, Alabama. Slavery was still legal in the southern United States, but importing new slaves into America had been outlawed in 1808.

In his journal, Captain Foster described purchasing the captives using “$9,000 in gold and merchandise.”

As this replica shows, the enslaved Africans were locked, naked in the cargo hold of the Clotilda for two sickening months. When they arrived in Mobile, they were handed over to Timothy Meaher and several others. Captain Foster claimed he then burned and sank the Clotilda, but exactly where remained a mystery.

Until 2018, when a local reporter, Ben Raines, found the Clotilda in about 20 feet of water not far from Mobile. He’d been searching for seven months, following clues in Captain Foster’s journal.

The exact location hasn’t been made public for fear someone might vandalize the ship. But last year, the Alabama Historical Commission gave maritime archeologist James Delgado, who helped verify the wreck, permission to take us there.

Anderson Cooper: So the Clotilda came up this way?

James Delgado: Straight up here, practically in a straight line after they dropped off the people, and then on one side of the bank, set her on fire and sank her.

Anderson Cooper: So he was trying to destroy evidence of a crime?

James Delgado: Yes.

The bow of the Clotilda is not far from the surface, but the water’s so muddy, the only way to see it is with a sonar device.

MAN: Sonar is on. Zero pressure. Good to drop.

Anderson Cooper: So we’re almost over it now?

James Delgado: Yeah, we’re coming right up on it.

MAN: So, that’s the bow right there?

Anderson Cooper: That’s it right there?

James Delgado: Yes.

Anderson Cooper: Oh, you can see it like that?

James Delgado: Yeah.

Anderson Cooper: You can see it totally clearly. I mean, that’s the ship?

James Delgado: Yes. Yeah, that’s Clotilda.

On sonar, the bow is clearly defined, as are both sides of the hull. The ship is 86 feet long, but the back of it, the stern, is buried deep in mud. Those two horizontal lines are likely the walls of the cargo hold where the enslaved Africans had been packed tightly together, on the voyage from West Africa.

Anderson Cooper: So the hold where people were held, how big was that?

James Delgado: In terms of where people could actually fit, five feet by about 20 feet.

Anderson Cooper: Wait a minute. It was only five feet high? So people could barely stand up in this hold?

James Delgado: Yes.

Diving on the wreck is difficult. Underwater there is zero visibility. You can’t even see the ship, Delgado’s team has only felt it with their hands. They call it “archeology by Braille.”

This is the only image our camera could pick up — a plank of wood covered with what looks like barnacles.

Delgado and state archeologist Stacye Hathorn, showed us some of the artifacts they retrieved. This plank of wood is likely from the hull of the ship. And this iron bolt, with wood attached, shows evidence of fire damage.

Stacye Hathorn: You don’t see the grain of the wood.

James Delgado: It basically makes a briquette.

Anderson Cooper: So this is evidence clearly of, that they tried to burn the ship?

Stacye Hathorn: Yes.

James Delgado: Yes.

The enslaved Africans were taken off the ship before it sank, but Delgado says there could still be DNA from some of them in the wreck.

James Delgado: You will find human hair. You can find nail clippings. Somebody may have lost a tooth–

Anderson Cooper: You could still find human hair in the wreck of the Clotilda?

James Delgado: Yes.

The state of Alabama has set aside a million dollars for further excavation to determine if the Clotilda can ever be raised from the riverbed. The ship may be too damaged or the effort too expensive.

Mary Elliott: I think what’s extremely important for folks to understand is that – that there was a concerted effort to hide these things that were done.

Mary Elliott oversees the collection of slavery artifacts at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Mary Elliott: It’s important that we found the remnants of this ship, because it, for African Americans, it’s their piece of the true cross their touchstone to say, “We’ve been telling you for years. And here’s the proof.”

Remarkably, many of the descendants still live just a few miles from where the Clotilda was discovered. This is Africatown. Founded around 1868, three years after emancipation, by 30 of the Africans brought on the Clotilda.

Joycelyn Davis has organized festivals to honor Africatown’s founders. One of whom was her great great great grandfather, Charlie Lewis. Last year she took us to the street he lived on, called Lewis Quarters.

Anderson Cooper: So pretty much everyone on this street can trace their lineage back to Charlie Lewis–

Joyceyln Davis: Yes. Everyone here is related.

Anderson Cooper: Wow.

Joyceyln Davis: Yeah.

Lewis and some of the others got jobs at a nearby sawmill, owned by Timothy Meaher, the same man responsible for enslaving them.

Joyceyln Davis: I mean, they worked for, like, a dollar a day. And so they saved up their money to buy land.

Cudjo Lewis also worked at the Meaher’s sawmill. This rare film shows him in 1928, by then he was in his 80’s and one of the Clotilda’s last living survivors.

He helped found this church in Africatown. The same church his descendants still attend today.

Anderson Cooper: After emancipation, it seemed so unlikely that a group of freed slaves could pool their resources and build a community. I mean, that’s an extraordinary thing.

Mary Elliott: There’s this thing we say about making a way out of no way.

Anderson Cooper: Making a way out of no way?

Mary Elliott: When these folks were forced over here from the continent of Africa they didn’t come with empty heads. They came with empty hands. So they found a way to make a way. And they relied on each other. And they were resilient.

Africatown is the only surviving community in America founded by Africans and over the decades it prospered. There was a business district. The first Black school in Mobile, and by the 1960s, 12,000 people lived here.

Lorna Gail Woods: They built a city within a city. And that’s what we can be proud of.

Cassandra Wallace: We had a gas station. We had a grocery store…

Darron Patterson: Drive in…

Cassandra Wallace: …post office, all that was a booming area of Black-owned business.

But today those Black-owned businesses are gone. An interstate highway was built through the middle of Africatown in the early 1990s, and the small clusters of remaining homes are surrounded by factories and chemical plants. Fewer than 2000 people still live here.

The Smithsonian’s Mary Elliott took us to Africatown’s cemetery, where some of the Clotilda’s survivors and generations of their descendants are buried.

Anderson Cooper: No matter where you go in Africatown, you can hear factories and industry and the highway.

Mary Elliott: There is this constant buzz. It’s a buzz you hear all the time, day and night. And it’s a constant reminder of the breakup of this community.

The descendants we spoke with hope the discovery of the Clotilda will lead to the revitalization of Africatown and they’d like the descendants of Timothy Meaher, the man who enslaved their ancestors, to get involved.

According to tax records, Meaher’s descendants still own an estimated 14% of the land in historic Africatown, their name is on nearby street signs and property markers. Court filings indicate their real estate and timber businesses are worth an estimated $36 million.

But so far the descendants we spoke with say no one from the Meaher family has been willing to meet.

Darron Patterson: I don’t think it’s something that people want to remember.

Caprinxia Wallace: Because they have to acknowledge that they benefit from it today.

Pat Frazier: That they benefited, that’s it. That they benefited. And they don’t want to acknowledge that.

Anderson Cooper: People don’t want to look back and acknowledge it.

Pat Frazier: They don’t want to acknowledge that that’s how part of their wealth was derived.

Darron Patterson: Big part–

Pat Frazier: And that, on the backs of those people.

Anderson Cooper: What would you want to say to them? I mean, if– if they were willing to sit down and have, you know, have a coffee with you?

Jeremy Ellis: We would first need to acknowledge what was done in the past. And then there’s an accountability piece, that your family, for this many years, five years, owned my ancestors. And then the third piece would be, how do we partner together with, in Africatown?

Pat Frazier: I don’t want to receive anything personally. However, there’s a need for a lot of development in that community.

We reached out to four members of the Meaher family, all either declined or didn’t respond to our request for an interview.

One man who did want to meet the descendants is Mike Foster. He’s a 74-year-old Air Force veteran from Montana. While researching his geneaology, Mike Foster discovered he is the distant cousin of William Foster, the captain of the Clotilda.

Anderson Cooper: Had you heard of the last slave ship?

Mike Foster: No. No.

Anderson Cooper: What did you think when you heard it?

Mike Foster: I wasn’t happy about it. It was, it was very distressing.

Anderson Cooper: Do you feel some guilt?

Mike Foster: No, I didn’t feel any guilt. I didn’t do it. But I could apologize for it.

And last year, before the pandemic, that’s exactly what he did.

Lorna Gail Woods: Yeah, over 160 years have passed, and we finally–

Mike Foster: Hundred and sixty years.

Lorna Gail Woods: Yes.

Joyceyln Davis: This is a powerful moment. This is a powerful moment.

Mike Foster: So I’m here to say I’m sorry.

Lorna Gail Woods: Thank you.

Pat Frazier: Thank you.

In an effort to attract tourism to Africatown, the state of Alabama plans to build a welcome center here, but the descendants we spoke with hope more can be done to restore and rebuild this historic Black community and honor the African men and women who founded it.

Pat Frazier: So, I always think, my God, such strong people, so capable, achieved so much, and started with so little.

Darron Patterson: We have to do something to make sure that the legacy of those people in that cargo hold never ever is forgotten. Because they are the reason that we’re even here.

Since our story first aired, the city of Mobile has broken ground on a museum in Africatown that will open to the public in the fall.

Produced by Denise Schrier Cetta. Associate producer, Katie Brennan. Broadcast associate, Annabelle Hanflig. Edited by Patrick Lee.