PIC: One of the Pay Per Fetch water points at Biguli Trading Centre, Kamwenge district. (Credit: OWen Wagabaza)

HEALTH

“Don’t go ahead of me, you will stir the water and make it dirty,” Ayub Bakunda sternly tells his younger brother, Ziad Bakunda.

Although obliged and fetched the water near his brother, Anthony Baliruno refused: “I want ‘clean’ water yet this one is stirred and dirty,” he shot back, as he moved ahead of the pack.

Stunned by this brief episode, I move closer to Baliruno and ask him what they use the water for.

“It is for home use. We use it for bathing, cooking, washing and drinking. We only boil it when we have time."

Ironically, just about 100 metres away from the pond is a borehole long out of use. According to Baliruno, when the borehole broke down about six months ago, residents resorted to fetching water from the pond because they did not have the money to repair it.

This is Bulindo village, Mijwala sub-county in the central Ugandan district of Sembabule.

In Nakifuma Town Council, Nakulabye Zone boasts of two boreholes about 600m apart. But many a time, the area finds itself without safe drinking water as a result of breakdowns.

“There is a time when the two boreholes broke down at the same time, leaving us with no option but to go to shallow wells for water,” says Moses Ssendege, a resident.

Unfortunately, almost the entire country finds itself in such a scenario. Operation and maintenance of the available water facilities remains one of the biggest challenges to the provision of safe water in Uganda.

Currently, according to the Ministry of Water and Environment Ministerial Policy Statement of 2017/2018, the functionality rate for Uganda stands at 88% for rural areas and 89% for urban locations.

According to the 2015 National Service Delivery survey by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, out of the estimated 109,000 rural water point sources in Uganda, 16,350 sources are not providing water as expected.

The Assistant Commissioner for Rural Water Supply in the Ministry of Water and Environment, Eng. Christopher Tumusiime, says low functionality is a manifestation of operation and maintenance failures.

“Apart from leading to breakdown of sources, poor operation and maintenance contributes to contamination of water, hence undermining the goal of improving the quality of life through the provision of safe and clean water,” he says.

Baliruno and the Bakunda brothers fetching water from a shallow well in Kyamajanja Village. (Credit: Owen Wagabaza)

Pay Per Fetch model

One of the reasons for the collapse of water point sources is that communities are left to be passive recipients of water facilities. Yet, it is important that they play a pivotal role in the planning and implementation of their own water programmes and thus, play a central role in facilitating the functionality of water sources.

It is for this reason that several Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) activists have come up to advocate for the Pay Per Fetch model, a system where money for water is collected on a pay-as-you-fetch basis from everyone and at all water points in Uganda.

George Mugenyi is the manager of business development at Water for People Uganda, an NGO that is already implementing the pay-as-you-fetch model, argues that with Pay Per Fetch, there is an opportunity to collect revenue, which is used in maintaining the water systems and increasing its sustainability.

Eng. Peter Nyakaana, the deputy manager of Water and Sanitation Development Facility Central, a service delivery and funding mechanism aimed at developing water supply and sanitation infrastructure in rural growth centers, believes that the Pay Per Fetch model will attract investors to the water sector.

“The Pay Per Fetch model will also encourage private sector involvement in the water sector and this will ultimately improve on the access to safe water services," he says.

"The reason the issue of safe water has been left entirely to the government and NGOs is because it is not profitable, and this has repelled possible investors in the sector."

Nyakaana adds: “The model will also play a role in fighting the unemployment challenge in the country. It encourages entrepreneurship as it creates jobs for water point caretakers, operators, collectors and mechanics."

Gilbert Byamugisha is the manager of Central Umbrella of Water and Sanitation Authority, one of the six umbrella organisations that were set up to mainly handle operation and maintenance challenges in piped water supply systems in rural growth centers and small towns.

He says it is already a big challenge in making sure that people get water in places where water has been considered a free resource.

“There are a number of operational challenges, and people who expect to get free water are unfortunately not served. And even when they are served, the service is not that top-notch in terms of quality,” Byamugisha weighs in.

“When you look at the gravity flow schemes and hand pumps where payment is not considered as a priority, the beneficiaries experience very poor quality service. Whenever there is a small technical issue, it is difficult to attract a technical person to come and rectify it because there is no money.

"It is now coming out clearly that at whatever level, you cannot do away with paying for water," he adds.

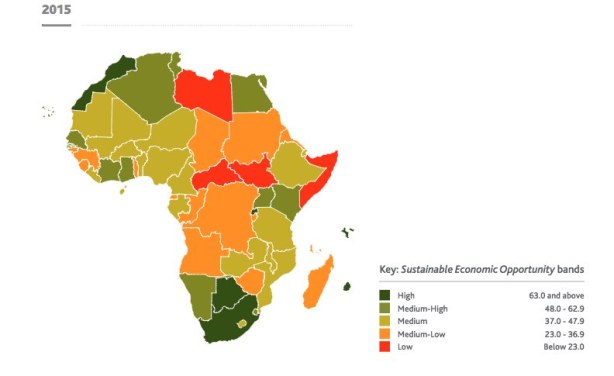

Moses Ssenkatuka, a WASH activist, says that Pay Per Fetch is the only way Uganda will attain the Vision 2040 target of piped water supplies throughout the country and Sustainable Development Goal 6, which calls for universal access to water and sanitation for everyone wherever they are.

“With Pay Per Fetch, not only will there be revenue to maintain the system, there will also be profits that can be used to expand the system as well as bring in affordable modern technology,” says Ssenkatuka.

An out-of-use hand water pump in Kyamajanja Village, Sembabule. The residents have since resorted to fetching water from a shallow well. (Credit: Owen Wagabaza)

How sustainable is the model?

One of the biggest challenges to the Pay Per Fetch model is the issue of sustainability, especially in terms of affordability, with many arguing that a huge percentage of the population in Uganda live below the poverty line and as such, cannot afford to pay for water.

Stephen Ssempebwa, a lecturer of Rural Development at Makerere University, says the model cannot work in Uganda today when people’s incomes are still low.

“It cannot work. Any one advocating for paid water throughout the country is an enemy of safe water coverage in Uganda. People are poor and cannot afford even the basics in life. Because they have no money, they will shun the safe water points and go for the shallow wells,” he argues.

According to the Uganda Poverty Assessment 2016, the proportion of the Ugandan population living below the national poverty line stands at 19.7%. The same report notes that 34.6% of the population lives on $1.90 (about sh7,000) or less per person per day.

WASH activist Ssenkatuka says that for the model to succeed, it is important that the price of water is reached at together with the community.

“If the price of water is set with the input of the community, the challenge of affordability cannot arise. There is a lot of wasteful spending in rural areas. People waste a lot of money on alcohol and marrying more women. There is no way a family can fail to raise sh50 or 100 for a jerry can of water if the price is arrived at democratically,” he explains.

To George Mugenyi, massive sensitization and attitude change are vital aspects that have to be looked at if the model is to succeed.

“When we started out it in Biguli sub-county in Kamwenge district in 2013, there was resentment towards the idea because people were used to free water, which was not sustainable. We embarked on a massive sensitisation drive and with time, we started seeing a change in people’s attitude and as of now, over 85% of the population has embraced the Pay Per Fetch model,” Mugenyi says.

Vision 2040

Simeon Komaho, the LC3 chairperson of Biguli sub-county, says that government intervention is important through the provision of the necessary infrastructure, such as electricity.

“Our water pumps are running on diesel, which is expensive and this makes a jerrycan of water cost sh100, but it can be far less if water pumps are running on electricity, which is cheaper. In fact, for hand water pumps, a jerrycan can cost as low as sh50,” he says.

According to Eng. Tumusiime, to achieve Vision 2040, the water ministry is looking at changing from hand pumps to more improved technologies.

“As a strategic direction, we are looking at technologies such as mini solar pumps that would not only ease the time spent to get water, but also have management systems that are more organised, can measure the amount of water being supplied in the system, are able to collect revenue, which same revenue would be used to facilitate the people running the system, buy the spares and pay for the technical support."

|

Job creator

Although the government and NGOs encourage the formation of management committees at each water point to ensure sustainability of community water systems, many of them have been found to be ineffective.

“We pay sh2,000 every month for the purpose of making sure that there is money in case of a breakdown. Unfortunately, that is not the case," reveals Nnalongo Zubeda, a resident of Nakulabye Zone in Nakifuma.

"Whenever the borehole breaks down, the chairman moves around collecting money for repair. At times, we can go for two weeks before raising the money needed for repair."

With the Pay Per Fetch model however, the water point is directly the in-charge’s source of livelihood, and as such, it is dependent on the system running. The more water people collect, the more money the in-charge makes. No water, no money.

To get a capable in-charge, the donor agency [government or NGO] behind the water point invites those interested in running the water point to apply for the job, after which they sit for the interviews from which they select the best.

In Biguli, under Water for People, Obed Mwesigwa mans the Bitojo-Byantumo- Nyabubaale water facility and earns sh400,000 per month after deducting all the maintenance costs, which is not a bad figure in a village setting.

“All I have to do now is to run the facility well so that it not only feeds me, but also provide safe water to Biguli residents on a permanent basis,” says Mwesigwa.

With an estimated 109,000 rural water point sources in Uganda according to the 2015 National Service Delivery survey by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, and with the country grappling high unemployment rates, the Pay Per Fetch model would make 109,000 jobs overnight.

With 15% of the water point sources not working due to operation and maintenance challenges, the model, which guarantees sustainable safe water coverage, is something that needs to be looked at with a keen eye from both the government and the NGO world.